by Kevin Barrett

In the game of running, the marathon represents a most treasured of distances; an exceptionally difficult test of endurance and will in the quest for one of life’s great bucket list items.

Finish the grueling 42.2 km route and the months of intensive training and personal sacrifices made along the way gain you membership into an exclusive club representing just one percent of the population.

Those are tall odds, but on 12 occasions Terry Thorne successfully ran into that club, part of a career that started in Saint John with her first race – a 5-miler as part of Marathon By The Sea (MBTS).

But those odds paled in comparison to what she’s faced in the game of life. In 2007, she suffered a brain aneurysm which almost killed her.

Through her nine years of recovery, with all of the associated ups and downs, she’s used lessons gained through running, combined them with a fierce personal determination and engaged in the fight for her life.

“Never Never Never Give Up,” reads the sign in her room at the Shannex Parkland In the Valley nursing home in Quispamsis, her home since December, 2012. It served as the site for a recent interview where she talked about her running, her battles and her role as Honorary Race Marshall for the 2016 Emera Marathon By The Sea.

“To me, it is a miracle I can walk, that I can move,” she said. “I know it is a miracle I am here. I am amazed.”

During Marathon By The Sea, she will put together some thoughts for the runners near the start line in a race that means so much to her. She never competed in the full marathon at MBTS but on Aug. 13, 2006, she posted a 1:49.41 in the half marathon, 151st in the 564-runner field and 11th of 83 runners in the women’s 40-49 category.

In fact, MBTS was her first race, the place where she got hooked and she ran other routes many times.

“I ran five miles,” she said of those first steps. “I looked around and thought that if anyone was going a half marathon, they were bananas.”

Next month, if all goes well, she’ll take part in one of the water stations along the route and the overall experience promises to rate as one of her great days.

Running, in many ways, has served Terry as a valued friend, a reliable ally as she faced the daunting physical and emotional challenges that started in 2007, shortly after she completed her 12th marathon.

It was then she experienced her first headaches as she trained for the full marathon in Saint John , part of a qualifying attempt for the 2008 Boston Marathon.

She was 43, a project coordinator for Irving Oil and running was a joyous activity to keep her body fit and her mind alert.

As the headaches persisted, she knew they needed to be checked out. Doctors ultimately found a large aneurysm on her brain stem. It was pressing on her optic nerve.

In an interview with Kathy Kaufield of KV Style, Terry detailed a risky 16-hour surgery in London, ON during which surgeons clinically killed her for 27 minutes through induced hypothermia.

Although the procedure successfully treated the aneurysm, she required a 2nd surgery in Toronto, ON and suffered two strokes that left her paralyzed.

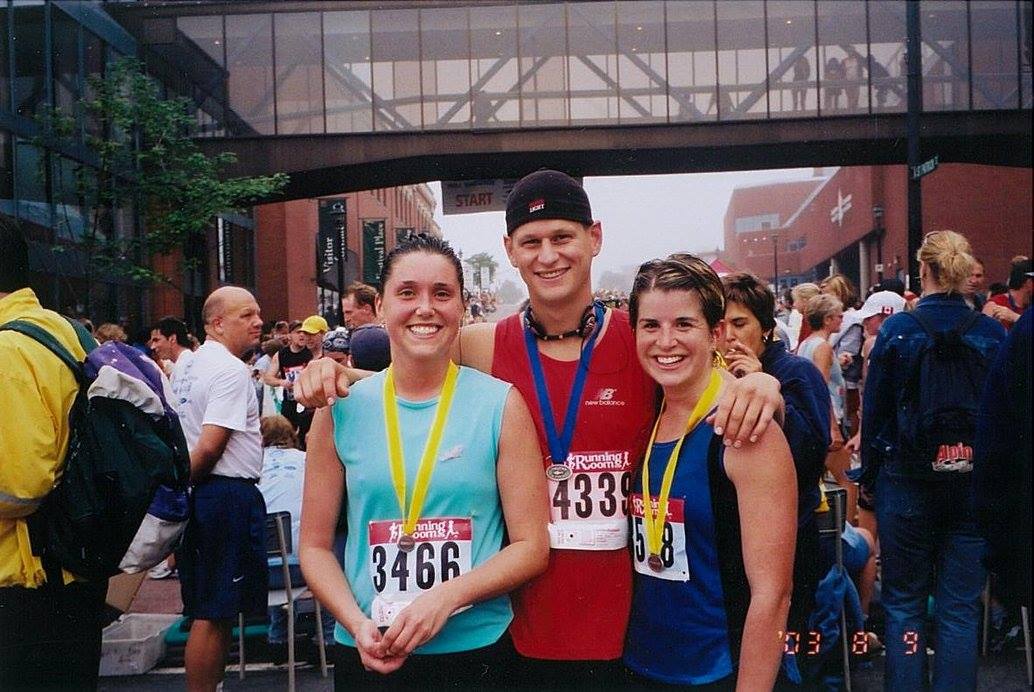

These days, outside her Shannex apartment sits a small, yet profound display that includes a photo box featuring photos of Terry running in the Fredericton Marathon and racing powerfully in the Marathon by the Sea half marathon. The display includes a finisher’s medal.

Inside her apartment are several photos of her children Brittany and Billy, and one of Terry and her husband Bill during a trip south one year.

There are also several signs, prominently placed on her wall.

There are also several signs, prominently placed on her wall.

They read as follows:

“Never, Never, Never, Give Up.”

“Believe in Miracles.”

“Dream it, Believe it, Live it.”

They are more than letters strung together; they symbolize her fighting spirit.

After the initial surgery and the strokes, she required a feeding tube and a wheelchair. Her speech was affected. She started her long recovery at the Stan Cassidy Centre in Fredericton, a five-and-a-half month stay that included nine rehab classes each day during the week. She wanted and received more on weekends to assist her progress.

Initially, she required a feeding tube and a wheelchair. Her speech was affected.

Yet, the dedication was working and the efforts were paying off. By October 2008, she walked 10km in the KV Challenge Marathon. She was able to drive and most days, she’d walked on her treadmill for two hours.

Over time, though, the headaches returned. Her balance became unstable. Her eyes bothered her.

This time, a three cm aneurism was found – more surgery, more rehab.

The road was growing longer, but there was no quit in Terry despite what seemed like a return trip to the start line of her recovery.

Ultimately, she moved to the Shannex facility in Quispamsis, needing assistance for almost everything.

She remembered her time in the Stan Cassidy Centre, where she’d work hard and try to encourage others to push their limits.

It represented her personal mantra.

“I was not willing to accept that I would be dependent on someone else,” she said. “I saw some of the others trying, but I would get so mad when they gave up.”

When Terry started to make strides, it was not always easy or pretty.

Once, shortly after her feeding tube was removed, she was so focused on eating from a bowl she grabbed a spoon and went for the meal in front of her. Only problem was her motor skills weren’t developed enough at that point to hold the spoon and put the food in her mouth. No matter, she tried and tried and tried, with food landing everywhere except where it was supposed to go.

She laughs now at the process but she would not give in until she could eat. She has not and will not quit.

“They gave me less than one percent chance to survive,” she said. “I was not going to accept that without a fight. More people have to do that.”

Another time, one exercise required her to touch a wall with her hand while standing up.

It was a long, difficult process but using her never quit philosophy, she conquered that task as well.

“I’ll never forget how excited I was to touch that wall,” she says. “It felt like I won a million dollars.”

She pays tribute to everyone who has helped her, acknowledging it was tough to let others assist and that she can be stubborn. That salute includes the staff at Embassy Hall at the Shannex facility.

“I am so grateful for so many people who have inspired me and who have helped me fight and get to a world I never knew,” she said.

She’s vocal now, a sharp contrast to her reserved nature prior to her injuries. Seems her opinionated, boisterous nature is one positive of a tough situation. It allowed to express her drive and tell others what she was going to do.

Running is a supportive crutch to lean on, a metaphor for determination.

Almost every day, she takes her walker and makes her way around the Shannex facility.

It was one lap at first and slowly, over time, the distances increased, a process many runners can identify with – gradual buildup in search of a longer goal.

Now, she aims for 22 laps, each measuring a half a step over 90 metres. The laps combine for two kilometres and on a good day, she can conquer the goal in three or four sessions.

She keeps a journal in a small well-used black book, as many runners did in the days before Garmins and other GPS devices. In her notes, she rates her performance, the good and not so good, the progress and the challenges.

The lessons learned apply now as much as they did when she was attempting to qualify for the Boston Marathon.

Instead of evaluating kilometer splits, she measures the circuit of her new home, continuing the hardest fight of her life. Almost a decade ago, she was unable to walk, talk, move much at all. She faced long odds.

She be on hand on race day to display that long odds can be overcome.

Never Never Never Give Up!

So with the assistance of Terry Blizzard and the great staff at Afterburn, Bill has lost a remarkable 47 pounds and is feeling better than ever.

So with the assistance of Terry Blizzard and the great staff at Afterburn, Bill has lost a remarkable 47 pounds and is feeling better than ever.